:::info Authors:

:::

Table of Links

2 INTERACTIVE WORLD SIMULATION

3.1 DATA COLLECTION VIA AGENT PLAY

3.2 TRAINING THE GENERATIVE DIFFUSION MODEL

4.1 AGENT TRAINING

4.2 GENERATIVE MODEL TRAINING

5.1 SIMULATION QUALITY

5.2 ABLATIONS

7 DISCUSSION, ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS AND REFERENCES

ABSTRACT

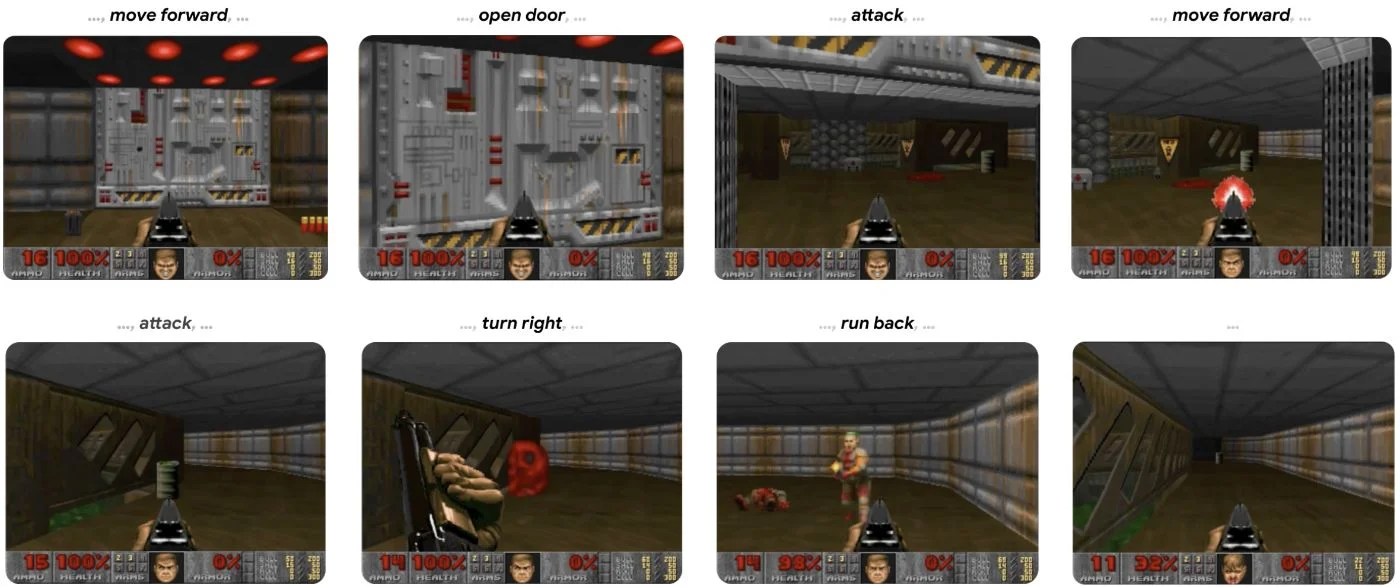

We present GameNGen, the first game engine powered entirely by a neural model that also enables real-time interaction with a complex environment over long trajectories at high quality. When trained on the classic game DOOM, GameNGen extracts gameplay and uses it to generate a playable environment that can interactively simulate new trajectories. GameNGen runs at 20 frames per second on a single TPU and remains stable over extended multi-minute play sessions. Next frame prediction achieves a PSNR of 29.4, comparable to lossy JPEG compression. Human raters are only slightly better than random chance at distinguishing short clips of the game from clips of the simulation, even after 5 minutes of autoregressive generation. GameNGen is trained in two phases: (1) an RL-agent learns to play the game and the training sessions are recorded, and (2) a diffusion model is trained to produce the next frame, conditioned on the sequence of past frames and actions. Conditioning augmentations help ensure stable auto-regressive generation over long trajectories, and decoder fine-tuning improves the fidelity of visual details and text.

1 INTRODUCTION

Computer games are manually crafted software systems centered around the following game loop: (1) gather user inputs, (2) update the game state, and (3) render it to screen pixels. This game loop, running at high frame rates, creates the illusion of an interactive virtual world for the player. Such game loops are classically run on standard computers, and while there have been many amazing attempts at running games on bespoke hardware (e.g. the iconic game DOOM has been run on kitchen appliances such as a toaster and a microwave, a treadmill, a camera, an iPod, and within the game of Minecraft, to name just a few examples1 ), in all of these cases the hardware is still emulating the manually written game software as-is. Furthermore, while vastly different game engines exist, the game state updates and rendering logic in all are composed of a set of manual rules, programmed or configured by hand.

\ In recent years, generative models made significant progress in producing images and videos conditioned on multi-modal inputs, such as text or images. At the forefront of this wave, diffusion models became the de-facto standard in media (i.e. non-language) generation, with works like DallE (Ramesh et al., 2022), Stable Diffusion (Rombach et al., 2022) and Sora (Brooks et al., 2024). At a glance, simulating the interactive worlds of video games may seem similar to video generation. However, interactive world simulation is more than just very fast video generation. The requirement to condition on a stream of input actions that is only available throughout the generation breaks some assumptions of existing diffusion model architectures. Notably, it requires generating frames autoregressively which tends to be unstable and leads to sampling divergence (see section 3.2.1). Several important works (Ha & Schmidhuber, 2018; Kim et al., 2020; Bruce et al., 2024) (see Section 6) simulate interactive video games with neural models. Nevertheless, most of these approaches are limited in respect to the complexity of the simulated games, simulation speed, stability over long time periods, or visual quality (see Figure 2). It is therefore natural to ask:

\ Can a neural model running in real-time simulate a complex game at high quality?

In this work we demonstrate that the answer is yes. Specifically, we show that a complex video game, the iconic game DOOM, can be run on a neural network (an augmented version of the open Stable Diffusion v1.4 (Rombach et al., 2022)), in real-time, while achieving a visual quality comparable to that of the original game. While not an exact simulation, the neural model is able to perform complex game state updates, such as tallying health and ammo, attacking enemies, damaging objects, opening doors, and persist the game state over long trajectories. GameNGen answers one of the important questions on the road towards a new paradigm for game engines, one where games are automatically generated, similarly to how images and videos are generated by neural models in recent years. Key questions remain, such as how these neural game engines would be trained and how games would be effectively created in the first place, including how to best leverage human inputs. We are nevertheless extremely excited for the possibilities of this new paradigm.

\

\

\

:::info This paper is available on arxiv under CC by 4.0 Deed (Attribution 4.0 International) license.

:::

\ \